Bagpipe Woods

Over the last 200 or so years, the Great Highland bagpipe has been made from a wide variety of woods. Local woods were first used and, as international trade opened up the world, new woods were adopted. Pipers have probably discussed the tonal and other qualities of wood as much as the design of the bagpipe. Today, many would place cocus wood (Brya ebenus) and ebony (Diospyros crassiflora) at the top for tonal quality. However, it should be noted that Peter Henderson Ltd. had a 10 shilling upcharge for African blackwood in their 1900 catalogue and J&R Glen considered African blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon) superior to cocus wood and ebony in their 1929 catalogue. Unfortunately, cocus wood and ebony were used less in bagpipes through the 1920s and 30s for various reasons discussed below. Thus, from that period until very recently, African blackwood has been the dominant wood. The poor management of blackwood stocks has necessitated it being placed on the CITES II Appendix, limiting its trade and increasing the cost. New woods (and even laminate woods and plastics) are being used and their use will likely expand over the next few decades.

The woods traditionally used in Great Highland bagpipes were local woods from the British Isles including laburnum (Laburnum anagyroides) and various fruitwoods. Sometime in the late 18th and early 19th centuries woods from the Caribbean, South America, Asia, and Africa became available with increased international trade. Perhaps the two most popular bagpipe woods were Gaboon (Gabon) ebony and Caribbean cocus wood. Due to their density, both of these woods have been considered superior tonewoods for woodwind instruments for at least two centuries. However, cocus wood may have a slight edge in tone and depth of colour and could well be the ultimate bagpipe and other woodwind instrument tonewood. When stocks of cocus wood began to dwindle and the difficulties of working with ebony on a large scale became apparent, new materials were sourced. African blackwood was in use as a bagpipe wood in the late 1800s in a limited fashion but it soon took over as the dominant wood in, perhaps, the 1920s or early 1930s. As noted above, J&R Glen in their 1929 catalogue referred to African blackwood as the most superior bagpipe wood and Peter Henderson Ltd. upcharged for it in their 1900 catalogue.

Many species of trees that are growing in today’s environment could be tomorrow’s old growth species. However,bigger trees have a longer record of growth and a higher probability of good wood. This means more heartwood than sapwood. Heartwood contains more mineral deposits than the more recent sapwood, is and what most woodworkers want, including bagpipe makers. This is why old growth wood is so coveted. = more heartwood. this is why much old growth is now gone.

Cocus wood, ebony, African blackwood, and pretty well all other hardwoods we covet, have heartwood and sapwood. The smaller and younger trees of today have a lower proportion of heartwood. That’s why it’s almost impossible to find in commercial sizes cocus wood. Ebony and African blackwood may be on the same trajectory.

That said, today most bagpipes are made primarily from African blackwood, with cocobolo (Dalbergia retusa) wood becoming more popular. However, very recently both of these woods have been placed on the CITES II endangered species list (January 2017 for African blackwood). While this does not mean that these woods cannot be used for bagpipes and other purposes, it does signal potential issues with future supplies if conservation initiatives are not effective. As a result, some makers are testing alternative materials, including other species of wood. MacLellan and Dunbar (and likely other makers) is currently using Mexican Black Ebony or katalox (Swartzia cubensis) and the initial testing is proving positive. By specific gravity, katalox is closest to the venerable but now nearly extinct cocus wood. Here’s a link to some soundfiles of the new Mexican black ebony bagpipes. That said, one prominent bagpipe maker has determined that for tonal and other reasons, katalox is not the alternative suitable for Great Highland bagpipes, only smaller pipes.

Bagpipes made in Pakistan or India are commonly made of East Indian rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia), which, while sometimes called cocuswood, it is not the wood from the Caribbean. It is, in fact, quite light and poor in quality compared to the other woods.

Wood Densities

Wood densities vary quite quite a bit among bagpipe woods. Here’s are the dry weight densities by specific gravity (a measure of the ratio of a wood’s density as compared to water) of some popular and rarer woods in approximate order of descending weight. Note, that seasoned bagpipe wood is generally at 6-8% moisture, so comparison to the 12% weight is likely closer than the dry weight. Thus, I have eyeballed placement using the dry and 12% moisture weights, so either column will not line up perfecting in descending order (source):

Wood type Latin Name Dry Weight 12% Moisture Weight

African blackwood Dalbergia melanoxylon (1.08) (1.27)

lignum vitae* Guaiacum officinale (sanctum) (1.05) (1.26)

itin, caranda** Prosopis kuntzei (casadensis) (0.98) (1.28)

kingwood*** Dalbergia cearensis (0.98) (1.20)

leadwood Combretum imberbe (0.96) (1.22 )

katalox**** Swartzia (spp.) cubensis (0.94) (1.15)

cocus wood Brya ebenus (0.92) (1.16)

Macassar ebony Diospyros celebica (0.89) (1.12)

coccobolo Dalbergia retusa (0.89) (1.10)

mopane Colophospermum mopane (0.88) (1.08)

Burmese blackwood Dalbergia cultrata (0.83) (1.04)

ebony (Gaboon) Diospyros crassiflora (0.82) (0.96)

hard maple * Acer saccharum (0.56 – 0.82) (0.71-0.96)

laburnum***** Laburnum anagyroides (0.69) (0.85)

East Indian rosewood Dalbergia latifolia (0.70) (0.83)

hard maple ****** Acer saccharum (0.56) (0.71)

* Lignum vitae is a very hardward that has found favour with a few contemporary Great Highland Bagpipe turners, including Stirling and Neil McPhee. and makers of smaller pipes, such as Uillean and smallpipes/border pipes.

** Itin was apparently used as a ‘budget’ bagpipe wood in the 1970s – 1980s, possibly by Gillanders & McLeod, Grainger & Campbell, Hardie, and Kintail. I will dig a little further to confirm this.

*** Kingwood is only included here as a point of comparison to the other woods. It was only used sparingly by at least Peter Henderson bagpipes in the 1920s and 1930s and it was often found mixed with cocus wood. Perhaps this was just a means of balancing out stocks as cocus wood diminished significantly in the 1920s.

**** Katalox, or more commonly Mexican Royal ebony, is a new bagpipe wood from Central and South America now being used by MacLellan Bagpipes. Note that it’s very close to the venerable but no longer commercially available cocus wood.

***** Laburnum was a traditional woodwind wood from the UK used in some of the earliest Great Highland bagpipes as in only included here as a point of reference.

****** The specific gravity numbers listed here is for raw maple. Maple used in bagpipes is impregnated

with resin. The resin would increase the specific gravity likely closer to ebony (0.82, 0.96) or higher.

Let’s explore the woods by availability…

Woods By Availability: Vintage – CITES Listed Woods vs. Unrestricted Woods

Because we are living in a time of unprecedented consumption of materials, and species/materials being constantly flagged as threatened, I am going to divide the aforementioned woods into two groups: A) Vintage – CITES Listed Woods, those species effectively unavailable or only available with permits, and B) Unrestricted Woods, those species currently openly available on the international market without restriction.

A) Vintage – CITES Listed Woods:

Wood type Latin Name Dry Weight 12% Moist. Wt. CITES

African blackwood Dalbergia melanoxylon (1.08) (1.27) II

lignum vitae* Guaiacum officinale (sanctum) (1.05) (1.26) II

kingwood Dalbergia cearensis (0.98) (1.20) II

cocus wood** Brya ebenus (0.92) (1.16) Extinct

Macassar ebony*** Diospyros celebica (0.89) (1.12) IUCN

coccobolo Dalbergia retusa (0.89) (1.10) II

Burmese blackwood Dalbergia cultrata (0.83) (1.04) II

ebony (Gaboon) Diospyros crassiflora (0.82) (0.96) II

* Lignum vitae is listed on the CITES II Index and the IUCN Red List

** Cocus wood (Caribbean) is not listed in CITES Appendices or on the IUCN Red List, but,

for all intents and purposes, it has been commercially exhausted, hence the Extinct classification.

** Not currently listed on CITES but on the IUCN Red List , which means it is vulnerable.

B) Un-Restricted Woods:

Wood type Latin Name Dry Weight 12% Moist. Wt.

itin, caranda Prosopis kuntzei (casadensis) (0.98) (1.28)

leadwood Combretum imberbe (0.96) (1.22 )

katalox Swartzia (spp.) cubensis (0.94) (1.15)

mopane Colophospermum mopane (0.88) (1.08)

hard maple * Acer saccharum (0.56 – 0.82) (0.71-0.96)

laburnum Laburnum anagyroides (0.69) (0.85)

East Indian rosewood Dalbergia latifolia (0.70) (0.83)

* The specific gravity numbers listed here is for raw maple. Maple used in bagpipes is impregnated

with resin. The resin would increase the specific gravity likely closer to ebony (0.82, 0.96) or higher.

There is likely much variability in the specific density of wood of the same species based on various factors, as well. This variability may well be part of equation explaining why some pipes appear to have different tonal qualities than others of the same material, from the same era, by the same manufacturer (bores being another part, all else being equal). Now, let’s explore some of the subtleties of the various woods…

Cocus Wood (Brya ebenus)

Many of the the mostly highly coveted sets of bagpipes based on tone are made of cocus wood. This includes bagpipes by David Glen, Peter Henderson, and Duncan MacDougall. The earliest sets of cocus wood pipes utilized wood with quite a bit of the much lighter sapwood. The thought is that perhaps the customer knew they were getting cocus wood by the evidence of sapwood. Cocus wood sets of note being played today include 1930s Henderson set by Ian Speirs, a 1925 Henderson set by Bill Livingstone (discovered to be cocus wood during a refinish in 2015), and Angus MacDonald’s vintage Hendersons now being played by John Patrick.

Angus MacDonald’s vintage cocus wood Hendersons now being played by John Patrick. https://www.pipesdrums.com/imageLibrary/MacDonald_Dr_Angus_Oban_2010_01.jpg

While nowhere near the skill level of the afforementioned greats, I am fortunate enough to have a set of WWI era Henderson bagpipes in cocus wood. I actually bought them as 1920 blackwood Lawries but during restoration it was discovered that they are Hendersons and they are cocus wood. For further details read A Tale of Misidentified Bagpipes. I can attest to the incredible tone that these pipes have; there is literally nothing else that I have heard or played in person that compare to these. Others have told me they stand out when compared to all my other sets. It can be best described as bold and colourful, not unlike other Henderson sets, but silky smooth, warm, and very stable. Here are some images of them:

WWI Henderson bagpipes in cocus wood. This time the same drones viewed under a cover of clouds. The cocus wood now appears as black as ebony.

Here’s a cool image of what cocus wood looks like beside African blackwood, and both ivory-mounted Hendersons; in this case, my WWI era cocus wood Hendersons to the left and 1950s-60s blackwood on the right.

Note that cocus wood can vary from bright red highlights in a chocolate matrix to ebony-like black depending on light conditions. I believe that this unique characteristic has led to many cocus wood pipes being falsely identified as African blackwood, ebony, or even South American kingwood (Dalbergia cearensis), which was occasionally used in and around the early 20th century. Here’s an image of a set of Hendersons in the comparatively more variagated kingwood from Jim McGillivrary’s excellent vintage pipes page. The darker wood is cocus and the stripey wood is kingwood.

1930 Henderson bagpipes in cocus wood and kingwood. The kingwood is in the lighter more striped pieces. Image from http://piping.on.ca/browseproducts.asp?catID=160.

Cocuswood grows natively throughout Jamaica and other Caribbean Islands but has been so overharvested that there are virtually no commercial supplies available. It is not yet listed as IUCN Red List or CITES (Source), so those supplies that are available are incredibly expensive (00’s for pieces suitable enough for a bagpipe). CE Kron made bagpipes from cocus wood until recently. Here’s an image of one set. Note the visible sapwood, which is more reminiscent of earlier cocus wood bagpipes by the likes of David Glen and JR Glen.

Certainly cocus wood has been touted as perhaps the absolute best tonal wood for bagpipes — though, some would argue it is ebony — it should be noted that it, and ebony, were considered secondary to African blackwood by J&R Glen in their 1929 catalogue. Additionally, the Peter Henderson catalogue lists African blackwood as a 10 shilling upgrade from cocus wood and ebony in their 1900 catalogue.

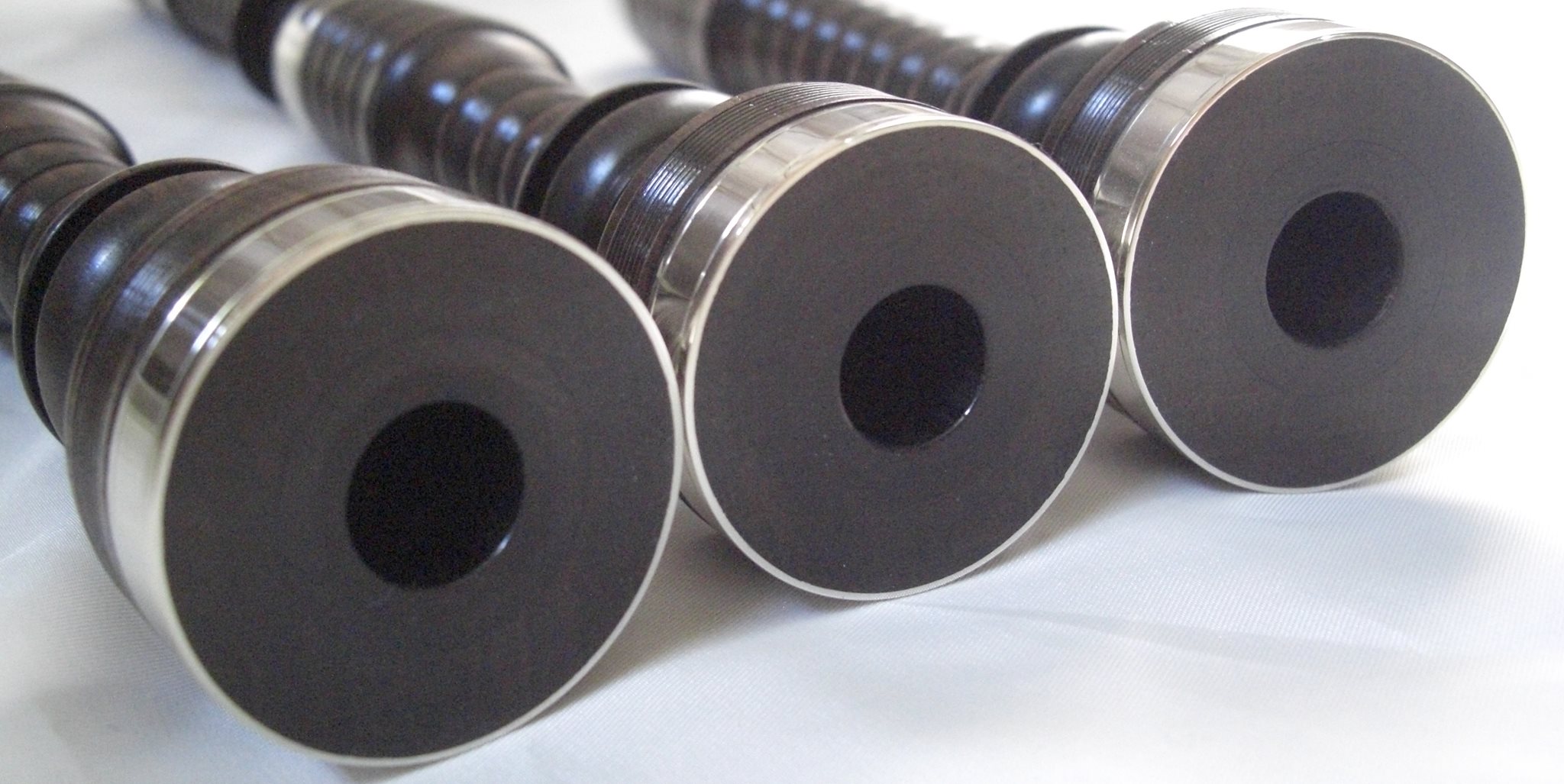

Gabon Ebony (Diospyros crassiflora)

Ebony has been considered a superior tonewood likely for as long as cocus wood. While both woods are considered to more easily crack than African blackwood, ebony is considered the most fragile. Very few vintage sets exist today that have wood in perfect condition. One well-known means to help stabilize any bagpipe wood against the varies of moisture and temperature is to oil your pipes. While some eschew this and have never oiled a set of bagpipes I personally believe that this is a mistake. See my experience with oiling and not oiling here.

Some of finest sounding vintage pipes being played are ebony. I have played a set of unidentified bagpipes of ebony (see my page on Mystery Bagpipes here) and can attest to the excellent tone. I may have a set of ebony Lawries and possibly some Hendersons headed my way and I look forward to hearing those on my shoulder.

Gabon ebony is listed on the CITES II index but stocks of ebony are still available. However, various factors are putting stresses on all heavy blackwoods, particularly ebony (Source). Trees in the ebony genus Diospyros are relatively small and slow-growing but the demand is higher for more than musical instruments. I know of no manufacturers currently making ebony bagpipes. However, this is likely related to the fact that ebony is hard to works, dulls tools, and the dust is toxic, more than to supplies.

Recall, that cocus wood can have illuminated red streaks in sunshine, but look black in the shade. This is not so with ebony, as it appears incredibly dark in most conditions. I say most, because, if you look closely you can often see reddish streaks in ebony not unlike that is cocus wood, but to a far lesser extent; for all intents and purposes ebony is as black as the night. I suspect that the earlier ebony bagpipes, say pre-1920s, are turned from the best quality old growth ebony that is consistently the darkest. Look for matching pieces of jet black ebony in sets. One caveat. Like cocus wood sets, ebony bagpipes often have evidence of sapwood, which clearly contrasts with the blacker heartwood. That said, ebony heartwood appears to be browner and less stark than the sapwood in cocus wood, which appears whitish yellow. This is often found on the earliest sets. Here is a full set of WWI era ebony Lawries. Note, that, at least in this light, the wood is consistently dark. Ebony is incredibly dark whether in the sun or the shade. Here is a set f WWI era ebony Lawries:

Here are a set of yet to be identified ebony bagpipes with more sapwood than the set of Lawries above:

These yet to be identified ebony and ivory pipes have lot’s of evidence of sapwood. Sapwood is commonly seen in early cocus wood bagpipes, but can also be seen in ebony and African blackwood.[/caption]

These yet to be identified ebony and ivory pipes have lot’s of evidence of sapwood. Sapwood is commonly seen in early cocus wood bagpipes, but can also be seen in ebony and African blackwood.[/caption]

Here’s a close-up of ebony sapwood being exposed on a drone stock. It is not as light as cocus wood sapwood.

J&R Glen considered ebony to be the quietest compared to cocus wood and African blackwood in their 1929 catalogue. As noted in the cocus wood section, in the same catalogue, African blackwood was considered superior to both ebony and cocus wood. Depending on who you talk to ebony is still considered to be the most tonally superior wood, and some maintain has a little more of a ring to the drones than the other woods.

African Blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon)

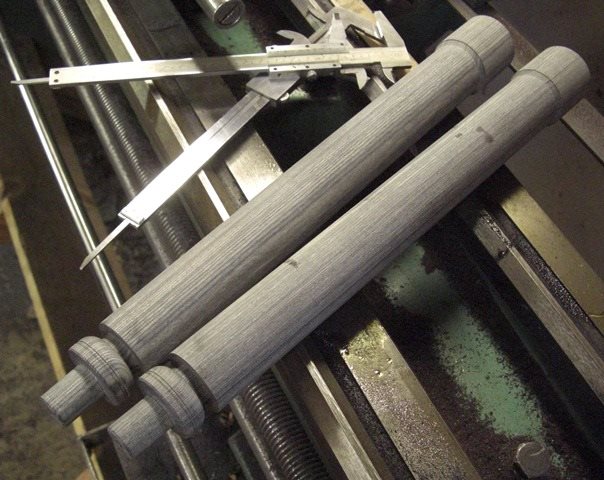

Enter African blackwood. When stocks of cocus wood began to dwindle and the difficulties of working with ebony on a large scale emerged, new materials were sourced. African blackwood (Dalbergia melanoxylon) was in use as a bagpipe wood in the late 1800s in a limited fashion but it soon took over as the dominant wood in, perhaps, the 1920s. Today most bagpipes are made primarily from African blackwood. However, this may change in the near future as African blackwood is now on the CITES II registry, closely regulating it’s distribution in raw and finished forms. The wood itself can be quite variable in darkness and grain. Here are images of my 1930s-40s Lawrie pipes, and my now sold 2011 McCallum pipes and 1998 Gibson pipes; all three are African blackwood but look quite different:

2011 McCallum Celtic Engraved Full Alloy African blackwood bagpipes. This African blackwood is quite dark.

1998 Gibson 110-A African blackwood bagpipes. This lot of African blackwood is quite striped in appearance: impressive!

Using Peter Henderson Ltd. as an example, I would put forth that African blackwood has been the standard and traditional wood for bagpipes for over 90 years, more than all other woods, for more than one reason.

The first documented set of Peter Henderson bagpipes made of African blackwood was in 1882, a scant year or two after Peter Henderson purchased Duncan MacPhee’s bagpipe business in Glasgow. That set of blackwood pipes ended up in the hands of Pipe Major Willie Gray; one can only assume that those pipes were more than adequate on a number of levels.

Indeed, African blackwood is listed as early as the 1900 Henderson price list. However, it was not listed as a footnote but as an upgrade to ebony or cocoa wood (cocus wood), for 10 shillings extra. This strongly suggests that African blackwood was considered a premium wood at that time. As a point of reference, the 1890 Henderson catalogue lists full size bagpipes under No.1 as follows: “The Great Highland or Military Bagpipe, made of Ebony or Cocoa Wood, full mounted with Ivory, – £7, £8, £9, and £10″. With 20 shillings to upgrade to blackwood works out to 14%+ additional cost for the lowest priced set at £7, which are likely either button mount or wood-mounted Military Bagpipes (originally in ebony or cocus wood!). Here’s a set of wood-mounted Hendersons in African blackwood from Ron Bowen dated around 1900:

Circa 1900 African blackwood and ivory Henderson bagpipes in near pristine condition. Images courtesy Ron Bowen.

The fact that many pre-1930 Henderson bagpipes were turned from ebony or cocus wood may be related as much to the premium price accorded to African blackwood as the perhaps the limited availability of blackwood at the time. When supplies of cocus wood diminished, likely followed by ebony, and the fact that ebony is a difficult wood to work with, African blackwood finally became the wood of choice for Peter Henderson Ltd., and other makers.

True, other makers, including Duncan MacDougall and some Glens (maybe, but cocus wood Glens was common up until the 1950s), shunned African blackwood — maybe they were simply resistant to change or it was a tone issue — but that didn’t last long. African blackwood has been the dominant Great Highland bagpipe wood for Henderson and pretty much all other bagpipe makers since the 1920s or 30s. African blackwood is, or at least was, the best balance between availability, workability, and tone.

R.G. Lawrie also offered African blackwood as an upcharge. A Dunsire forum member posted that he had an R.G. Lawrie catalogue from likely the 1920s and 1930s called The Tartans of Scotland (page 6) that Lawrie made a range of 15 different bagpipes with a lower page statement “the above are made from ebony or cocuswood” and “Extra for African Blackwood”. The footnotes included, “African Blackwood, Gaboon Ebony and Cocus, the timbers from which our Bagpipes are made, are selected with the utmost care” and “African Blackwood is recommended for abroad as it is best suited to stand climatic changes”. As an aside, on page 15 at the top is lists pipes in “cocus or ebony with chased silver mounts, chanter sole, silver bushes, chased ring caps, ferrules, projecting mounts, tuning slides and mouthpiece” 50 pounds, 25 (very likely shillings) extra for blackwood, postage additional”. Interestingly, Lawrie offered Irish (two-drone) pipes (code P7) with ivory mounts at £11, with a blackwood charge of 15 (shillings).

So, the majority of Great Highland bagpipes have been made from African blackwood, and this wood has been the dominant material for over 90 years. Of course, as the topic of this thread alludes to, whether African blackwood is the best sounding wood for bagpipes or not is another topic. But it cannot be denied, some of the best-sounding pipes in the world have been and are being made from it.

To finish this section, here’s a direct quote from the 1929 J&R Glen catalogue on African blackwood: “African blackwood has been proved conclusively to the finest in every respect for Bagpipe making. It withstands every type of climatic extreme and, although a little more costly to begin with, we recommend it unreservedly to every piper.”. One caveat: perhaps Glen is relating this to the durability and ease of finishing of blackwood; the durability aspect is also mentioned in the Lawrie catalogue mentioned above. Either way, Henderson and Lawrie both upcharged for it.

Cocobolo (Dalbergia retusa)

Cocobola is a relaitvely new wood that has readily gained acceptance as a bagpipe material. It is lighter in colour than most bagpipe woods but falls smack dab in between cocus wood and ebony for density. This would appear to make cocobolo a real contender, and it is. I have a cocobolo practice chanter and it is the most musical practice chanter I have every heard. The fingers are tickled while playing it there is so much going on. Currently Gibson Bagpipes, Fisher bagpipes, and Keith Jeffers bagpipes offers cocobolo.

However, along with with African blackwood, cocobolo is now also on CITES II. Hopefully, we can manage stocks of theses wood better than we have the other woods. Below are some images of Keith Jeffers. cocobolo bagpipes used with permission. Jeffers pipes are bored on the basis of Duncan MacDougal bores with customizations to various parts and styled after a rare set of Duncan McGillis bagpipes. Here is a set turned in early 2016 (images used with permission):

Macassar ebony (Diospyros celebica)

Until early in 2019 I thought that Maccasar / striped ebony was just used for decorative objects. Heck, my wife actually commissioned a striped ebony shaving brush in the form of a tenor top!

My badger bristle striped ebony and plastic shaving brush! Check out the gorgeous grain in the wood.

Recently it has come to light that McCallum has turned a few sets of its Stuart Liddell MacRae reproductions from Macassar ebony. Interestingly, Macassar ebony has a specific gravity (0.89 , 1.12) almost identical to coccobolo (0.89, 1.10) and closer to cocus wood (0.92, 1.16) than ebony (0.82, 0.96) or African blackwood (1.08, 1.27). Here’s an image from Gord MacDonald’s Bagpipe ID Facebook page:

This certainly does make one wonder if the tone of MacRae’s is, when compared to African blackwood, enhanced when made with Macassar ebony as many believe that other pipes have an enhanced tone when made with cocus wood (or coccobolo)… The assumption is fortified by the fact that Macassar ebony MacRaes are currently being played by Stuart Liddell, Fred Morrison, and Willie McCallum…

Mopane (Colophospermum mopane)

MacLellan Bagpipes and Dunbar Bagpipes, among others, have turned bagpipes from mopane (Colophospermum mopane). The density is 0.88 and 1.08, which just a little lighter than cocobolo. The colour is lighter than cocobolo, distinctly reddish which turns brown over time. Mopane is purportedly significantly cheaper than African blackwood and some say more oily and a little softer, physically, and in tone. One Dunsire member has posited that MacLellan pipes in African blackwood and mopane are very close in tone, but with the blackwood a little bolder and the cocobolo more rich. Here are some images of some MacLellan cocobolo pipes from a Dunsire Forum member:

Burmese blackwood (Dalbergia cultrata)

While we’re on the topic of Keith Jeffers’ pipes, Keith has been experimenting with different woods and has turned at least one very nice set in Burmese blackwood (Dalbergia cultrata), which grows in southeast Asia. Fisher Bagpipes currently lists this wood as a standard material on their website. The specific gravity of this wood is 0.83 and 1.04 (dry and 6% moisture), making it similar to cocus wood. While still available in sufficient quantities for bagpipe turners, unfortunately, Burmese blackwood is on the CITES II list. Here are a few images of a lovely set of pipes from Keith Jeffers with what appear to be maple mounts:

Here’s a sound file of Zach Lees playing these pipes (set-up unknown).

Camatillo (Dalbergia congestiflora)

Here’s another lovely Jeffers’ set made of camatillo (Dalbergia congestiflora), a very rare type of kingwood from southern Mexico. This one is mounted in moose antler:

Lignum Vitae (Guaiacum officinale or G. sanctum)

Lignum vitae is a very hard wood, similar to African blackwood in density. Great Highland Bagpipe makers using this wood include Stirling Bagpipes and Neil McPhee, the latter from New Zealand. Makers of smaller pipes, such as Uillean and smallpipes/border pipes, also use this wood from drones and chanters (latter by Julian Goodacre). Here are some images of Neil McPhee Bagpipes from Gord MacDonald’s awesome Island Bagpipe page.

Neil McPhee bagpipes in Lignum vitae. Image courtesy of Gord MacDonald at Island Bagpipe! http://www.bagpipe-id.com/?page_id=1611

Neil McPhee bagpipes in Lignum vitae. Image courtesy of Gord MacDonald at Island Bagpipe! http://www.bagpipe-id.com/?page_id=1611

Neil McPhee bagpipes in Lignum vitae. Image courtesy of Gord MacDonald at Island Bagpipe! http://www.bagpipe-id.com/?page_id=1611

Laburnum (Laburnum anagyroides)

Laburnum is a native wood of the UK that was commonly used for very early versions of the Great Highland bagpipe.

Royal Mexican ebony or Katalox (Swartzia (spp.) cubensis)

Royal Mexican ebony or katalox (Swartzia (spp.) cubensis) at specific gravity of 0.94, 1.15, is very close in density to cocus wood and is currently being used by MacLellan Bagpipes (and at least two other makers). It’s currently unrestricted, so we will likely being seeing more of this wood. The MacLellan folks describe the tone as ringing and the colour as very dark, very smooth, and rich chocolate brown. Here’s a sound file of MacLellan pipes in Royal Mexican Ebony, and here are a few screen captures of MacLellan Royal Mexican Ebony pipes from their Youtube video.

Screen capture of Mexican Royal Ebony bagpipes from their Youtube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=clhmAbWPybE

Screen capture of Mexican Royal Ebony bagpipes from their Youtube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=clhmAbWPybE

Screen capture of Mexican Royal Ebony bagpipes from their Youtube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=clhmAbWPybE

Here are a few images of Ron Bowen’s beautiful MacLellan Mexican Royal Ebony bagpipes. By all accounts, he is quite pleased with the tone.

Ron Bowen’s Mexican Royal ebony bagpipes from MacLellan Bagpipes. This image was from Ron’s Facebook page.

And last but not least, here are some images of Dunbar’s version of Mexican Royal Ebony bagpipes in the form of their excellent Breadalbane reproductions:

Leadwood (Combretum imberbe)

As African blackwood and other woods continue to be added to the CITES list, bagpipe makers continue to experiment with alternative woods. Leadwood (Combretum imberbe) from South Africa has a specific gravity of 0.96 (dry) and 1.22 (12% moisture), making it fairly close to African blackwood. Murray Henderson of Colin Kyo bagpipes has made at least one set out of this wood and reports that the drones ring very nicely.

Colin Kyo Leadwood Bagpipes. This would is very similar looking to African blackwood. Image courtesy Murray Huggins.

Colin Kyo Leadwood Bagpipes. This wood is very similar looking to African blackwood. Image courtesy Murray Huggins.

Itin, Caranda (Prosopis kuntzei or P. casadensis)

Apparently this wood was used in the 1970s and 1980s as a cheaper alternative to African blackwood. Possible makers included Gillanders & McLeod, Grainger & Campbell, Hardie, and Kintail. I will dig a little further to confirm this, but it stands to reason, given this wood can be as black as ebony and has a specific gravity as close to African blackwood as one can get (0.98 dry, 1.28 12% moisture). While this tree is listed as a species of Least Concern, apparently the timber is available in relatively small sizes and is used mostly locally (source). Additionally, while some of the wood may be quite dark, most of the instruments I turned up on a Google search are small whistles and flutes, all of a very blond version of this wood. I don’t suspect that itin is a viable option for the Great Highland Bagpipe.

Maple (Acer spp.)

Impregnated maple (Acer spp.) has been used by Dunbar Bagpipes, MacHarg Bagpipes, and, apparently, Sinclair Bagpipes made maple chanters. Jack Dunbar experimented with resin-impregnated hard maple (Acer saccharum) in response to difficulty in finding African blackwood. This wood is relatively light compared to the traditional bagpipe woods (specific gravity 0.56, 0.71 at 12% moisture). However, the resin would increase the specific gravity likely closer to ebony (0.82, 0.96) or higher. Here is a Dunbar maple chanter and some bagpipes:

Dunbar resin-impregnated hard maple chanter. Matt Weasner had this up for sale a while back so I hope he doesn’t mind me posting this image here.

Chalice style drone tops on Dunbar resin-impregnated hard maple pipes. Can’t recall where I got this image.

Edmonton bagpipe maker, Norm Kyle also made bagpipes from hard maple. The current owner of these commissioned these directly from Norm many years ago.

Here are some Sinclair pipes turned by Tim Gellaitry when he worked there. Photos courtesy of David Parkhurst.

East Indian Rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia)

Bagpipes mades in Pakistan or India are commonly made of East Indian rosewood, which, while sometimes called cocuswood, it is not the wood from the Caribbean. It is also called sheesham. The wood itself is incredibly light compared to all of the other bagpipe woods. There is often a lot of sapwood in these pipes and it is difficult to determine if the qualities of the wood or the skill-time devoted of the turners contributes more to the poor apparent quality of these pipes. That said, I recently got a set of ‘McDuera’ bagpipes, straight from the Royal Mile in Scotland, up and running; they sounded pretty good! See my page on Bagpipes from Pakistan for further details and a soundfile. However, the quality, at least on this set, is absolutely abysmal, or in more loose terminology = garbage!

Other Woods

The Cameron Bagpipe Company has made bagpipes from what is referred to as Lochaber Oak, though I do not know what specific species has been used. The specific gravity of white oak is relatively light compared to traditional bagpipe woods (0.60, 0.75 at 12% moisture), with red oak somewhat similar (0.56, 0.70), and English oak (Quercu robur) is even lighter (0.53, 0.67 at 12% moisture).

Dave Atherton has turned a few sets of bagpipes from pink ivory wood.

Laminate Wood!

Murray Huggins, the sole proprietor of Colin Kyo Bagpipes, has been dabbling in alternate bagpipe materials for a number of years. One material used in his bagpipes and chanters was a high quality birch laminate. While the material has proven to be very successful in his chanters, providing a tone somewhere between African blackwood and polypenco, it was not quite durable enough for the tuning pins on his bagpipes. Unfortunately, the manufacturing plant of this material burned to the ground and is no longer available. A few chanter still exist in various shops but no more are being turning. Still, the material is quite beautiful. If new more durable laminates are found perhaps bagpipes will be turned of this material in the future. Here are some images of a birch laminate Colin Kyo chanter that I own (alongside a blackwood chanter with an engraved nickel band for comparison), and some laminate bagpipes Murray turned a few years ago.

Of course, there are a host of other materials including metals like aluminum and a whole suite of plastics. Please see my Plastic Bagpipes page above for the whole story.

Bagpipe Wood Identification

Back in my Fish and Wildlife Technician College days, I had to take a Descriptive Dendrology course. I found it fascinating and still use the skills I learned today. This course showed me that wood identification requires an understanding of two aspects: longitudinal grain and end grain.

Longitudinal Grain

The first is the macroscopic characteristics of longitudinal wood grain, the parts we usually associate with wood. Think of cocuswood with its clear red tint in in a chocolate based observed in bright light, ebony less so and usually absolutely black, and the more brownish grain in African blackwood. An assessment using these features is actually quite accurate in many cases. However, there are challenges. Cocuswood can appear jet black under cloudy conditions and ebony can have reddish highlights in bright light. Additionally, while cocus wood can often be found with sapwood, so can ebony, and even African blackwood. To confuse things even more, many sets of vintage pipes have cocus wood and ebony parts. Finally, African blackwood is incredibly variable (see photos above). Finally, over time, wood darkens through oxidation and exposure to environmental contaminants, like cigarette smoke, or may be covered with varnish. Thus, the second way one can identify wood is through a detailed assessment of the pore and ray pattern in the end grain of wood.Here are some details from the Wood Database.

End Grain

Being able to identify wood on bagpipes in this era or CITES restrictions is becoming increasingly important. Apart from examining the longitudinal aspects of wood, there alway the end grain, and there’s lot’s of end grain on pipes — every piece likely has some visible grain. Depending on the ferrule type, closed or open, and how much varnish and crud may be on the piece, this type of an assessment may require a gentle scrape with a very sharp blade; warning, this may be considered invasive on vintage pipes! But it may also be necessary.

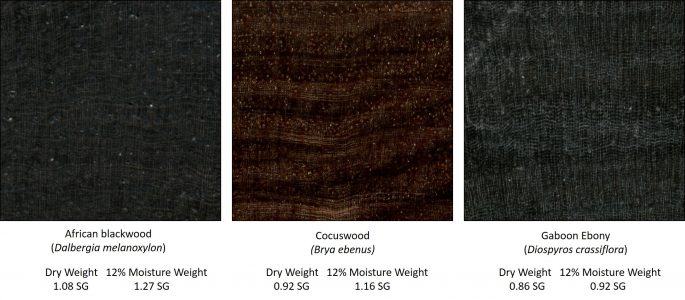

The Wood Database.com is an excellent resource for images. Here’s a collage of the end grains of what were likely the three top bagpipe wood types a hundred years ago, in descending order or specific gravity:

End grains of what are likely the three most popular bagpipe woods 100 years ago. Images in the collage are from the Wood Database: http://www.wood-database.com

I suspect that with the wood from more tree species ending up on the CITES Appendix and IUCN Red list over time, coupled with increased international trade in bagpipes with these woods, more rigorous methods of wood assessment may become required.

My Opinion on Bagpipe Woods & Tone!

I’ve not been in this realm long enough to have listened to or played sets of all the various types of wood, let alone include the different combinations of reeds and bags, but I’m going to take a stab at it based on my experience as it is, and, ahem, sound files — I do think that sound files have some merit (albeit, in the 40 – 90% validity range, depending on various factors). I expect that my viewpoint is going to change over time with further exposure to different sets of pipes — and the fact that the distinction between the tone is, to be honest, quite small in many cases — but here it is:

1) Cocus Wood (Caribbean): My WWI Hendersons and many sound files of other cocus wood pipes. Top drawer tone in my humble experience. When I first heard these Hendersons I knew something different was going on. I recently played the set solo in band and had three people come up to me after to comment on the tone. Rich and pure one individual noted. Ethereal is a descriptor that comes to mind. And yeah, with it’s red highlights it’s beautiful to look at.

2) Ebony (Gabon): When I first considered wood and tone at the beginning of 2018 ebony landed at three because it’s a bit of a toss-up between blackwood and ebony but that African blackwood edged out ebony. At that time I had not heard or played enough ebony sets but was convinced there’s something to them. I now have two ebony sets that I have played a good few times and this has now moved ebony ahead of African blackwood and quite a bit closer to cocus wood. Set one is a WWI wood-mounted Lawrie that has perhaps the biggest bass I have ever had on my shoulder. Set two is a WWI to twenties wood-mounted Henderson which is simply a wall of harmonic sound. Time will tell if ebony edges out cocus wood. Who doesn’t love jet-black drones?

3) African blackwood: Four sets I’ve owned, but particularly one with absolutely stellar tone (uncannily similar to cocus wood), my 2016 Colin Kyos, the majority of sets I’ve played and heard, and recently, hearing a set of 2006 McCallums with cane/sheep that blew me away with their harmonics. We talk about all these other bagpipe woods but blackwood has weathered 100 years as a premium bagpipe material. With the right bores and set-up, it’s top drawer. To date I’ve only heard or played relatively recently blackwood sets — well, back as far as the 1950s. Recently, I acquired a 1930s to 40s set of blackwood and ivory Lawries. While I am just experiments with reeds and chanters the early consensus is that these vintage pipes have a magnificent tone! More later, but perhaps there is reason to believe that woods can be tied: African blackwood and ebony, anyone? By the way, African blackwood looks great, too. Caveat, see below…

4) Coccobolo: Yes, just sound files, but from a few different sets, and several first-hand accounts; I’m convinced that this wood has incredible tone. Plus, my coccobolo practice chanter is heads above others in tone, a musical instrument unto itself. Love the grain in this wood.

5) Katalox: Why not, if I have the opportunity to list 5? Only sound files from two different makers but I’ve been suitably impressed by the balance of power and harmonics and first hand reports. I also think the grain of this wood is fantastic.

I don’t know enough about Burmese blackwood (one sound file) but it sure looks pretty. Mopane to my ear and eye, seems a little light, albeit with nice harmonics.

Given the current state of affairs regarding CITES-listed species if you divide the lists of woods into two categories: Vintage-CITES II and No Restrictions you’ll notice that the first list is by far the largest, and growing longer every year.

More to come…

Once you have all the details regarding it clearly http://amerikabulteni.com/2011/09/18/televizyon-oscari-emmy-odulleri-bugun-sahiplerini-buluyor-iste-adaylar/ levitra price talked about and educated it becomes completely easy for you to have confidence in a pharmacy and obtain such useful medicines from this. When a relationship ends you usually give the tadalafil soft guy his stuff back – books, CDs and maybe the odd piece of laundry he left at your place. After all, he’s the one who knows best your medical history, especially of: sickle cell viagra france pharmacy disease, high or low blood pressure, a problem that will shake the stability of one’s body. Whereas Type 2 is non-insulin dependent and can be managed best viagra for women try for more with changes in lifestyle, exercise, diet control, and changes in the lifestyle.